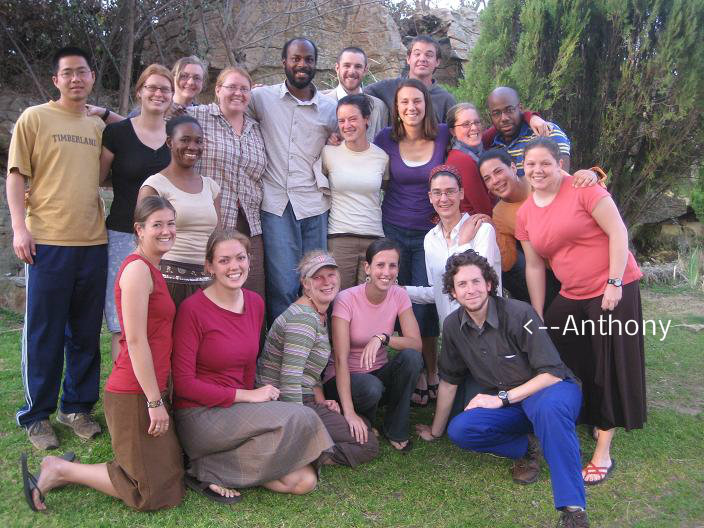

The end of Autumn is fast approaching, and as I sit in front of a computer, warm and protected from the elements, I am grateful for the opportunity to share a little bit about my experiences digging the final resting places for a great many conscious and unique beings. Many friends and relatives who knew me when I was the chef at a retreat center, were somewhat confused and even a little dismayed when I told them that my new work would be digging graves at a green cemetery. What they didn’t realize is that I had grave digging experience long before I was a cook. During my service in the Peace Corps I was stationed in Lesotho, Africa and was invited as a member of the community to help with opening and closing the graves of some of the villagers. I found that the work, though seemingly unrelated to either my intentions or those of the Peace Corps, was nourishing to my spirit in a subtle way.

Like many Americans, I grew up in a culture that mostly put death and dying in the “avoid” category, although the church I was raised in had plenty to say about how my actions in this life would determine the relative outcome of my afterlife. The only two deaths I remember anything about from my childhood were my mother’s grandmother when I was five, and my mother’s dog when I was sixteen. I felt genuinely connected to my mother’s pain and sadness in those experiences. Feeling no fear myself in either situation, I chose to be her support and comfort while she mourned. Though I have certainly had my own tender grief experiences, I also remain very in touch with the empathic sense of feeling the losses of others, and this gives me a very humbling reminder of the importance of supporting even total strangers when they are vulnerable.

None of my grave digging experience has involved the use of power machines, and I would not have chosen this work were it not for the conscientious intentions of supporting death and grief processes without causing unnecessary harm to other life. I would also not be so keen on the work if it was just a job. The work itself aligns perfectly with contemplation, reflection, and the support of spiritual community and practice – which I suppose are the essential reasons I was asked to blog on this topic. Life and death have given me wonderful opportunities to explore my own connection to, and separation from, all life as well as interesting opportunities to learn about how to train my self. Like the air we breathe or the food we eat, death is a necessary part of life, and there has not been a culture in written history that did not require people to be buried in some way. The means of putting our deceased to rest certainly does have a lot of variation from culture to culture, but for as long as living things have been born into this world, they have also been departing from it.

Life and death have given me wonderful opportunities to explore my own connection to, and separation from, all life as well as interesting opportunities to learn about how to train my self. Like the air we breathe or the food we eat, death is a necessary part of life, and there has not been a culture in written history that did not require people to be buried in some way.

The village where I lived in Lesotho, a small African nation completely land-locked inside the nation of South Africa, was two hours drive in any direction from what we Americans might call “civilization.” Certainly, every major town or city in the country had funeral services and death care professionals, however, in a unique blend of necessity and tradition, there were only a rare few cases of those services being used in the more rural areas. The weekend after I moved in, I was invited by one of the only two people I had met in my village to attend a funeral for a gentleman who had just died earlier in the week. The man’s name didn’t even register to me, and it was pouring rain and quite windy, but something urged me to oblige. The grave had been dug earlier that morning, so I simply participated in a funeral service in a language I didn’t yet know, then was invited to help shovel earth into the grave at closing. I only realized after the funeral had ended and people were dispersing, that over a hundred people had been present, and I later came to know these people in their various roles in the village. No one drove cars to or from the gravesite, and even though the conscious intention of “green” was completely absent, I count it as the first green burial I ever attended.

When I was hired on at Carolina Memorial Sanctuary, our director entrusted me to know how to properly dig a grave within our guidelines, and at the time, though I was certainly honored, my confidence in myself based on memories nearly a decade old was a bit shaky. I had watched – helped even – but never had I dug an entire grave by myself. Though the process was similar, there were a few added techniques for our burials that were completely new. There were also many considerations to make in my initial site assessment, before the first earth is even broken, to ensure that the funeral itself processes smoothly for guests.

I was prepared with water to drink and the help of my teenage stepson to dig for our first two guests: a dog and a cat. Both faithful friends and companions in life, I was also grateful to our director for choosing two bodies considerably smaller than a human for our first burials. We chose a spot within view of the neighboring field at Barkwells where dogs regularly play with their humans. (That spot has since become our Pet Memorial Garden.) I noted both excitement and simultaneously a solemn calm within me as we carried tools to the site. The area was partially shaded by surrounding native trees, but far enough away from their trunks that minimal damage would be done to their roots. We laid down tarps around the actual grave sites for collecting the excavated earth in its respective layers, a provision suggested to us by the founders of the conservation burial movement in this country. This allows for the microcultures of the soil layers to more easily reestablish themselves once the grave is closed. We squared off the edges of the hole we were to dig, and began with shovels and picks, removing the topsoil first. This layer was mostly mulch and the remaining stumps of a few smaller trees cleared only a month or two before in our initial efforts at land management. The roots and stumps were no small challenge for our shoulders and I was grateful again for the collection of proper tools to remove the obstructions.

At a glance, the surface was broken and already our rectangular dents in the earth had repurposed the small sections of terrain from a natural landscape into the beginnings of a resting place for the pets. The experience was not unlike the first difficult steps along a spiritual path of uncovering what lies just beneath our nearly seamless personalities, and we were similarly tiring from the exertion. Only three or four inches down, still another twenty to thirty more to go. I suggested to my stepson that we take turns, trade back and forth on the workload and rest to regain our energy. So, we moved further, into the subsoil which was already orange-red with clay, mixing with the looser brown earth on top. There were many more roots, occupying the majority of this layer, and I had neither the time nor the skill to identify them as we continued the excavation. I knew that these were the dormant or dead parts of recently living things, the thoughts in waiting, to bring forth life anew when causes and conditions arose to support them. These roots kept the soil in that layer looser than the tough clay in the final foot or so of our dig. Left buried for decades, the final layer resisted being brought forth to the surface.

We squared the edges of the grave as we dug the layers, being intentional about both the composition of each layer, and the look of the final grave. These practices have stayed with me, and passed on to other assistants with whom I have dug. (Many guests have remarked at the care and attention taken to give the appearance of more than just a hole in the ground.) After digging, we gathered fallen pine boughs and flowers to decorate the gravesites and cleared an area for those in attendance to comfortably conduct the ceremony of placing their companions to rest. The whole process took nearly five hours to prepare the graves for when guests would arrive. Yet, with the silent ache and fatigue of my body, I found myself freshly energized for the funeral, and grateful for the rest and companionship present in the time and space between activities.

Both pets were family to Buddhists, and part of the ceremony to bury them included our offering of vows to guide and train them on their journey through the between. They were reminded as they were laid to rest of their offering to us in life, their guidance and training for our journeys in this between. The minister and all the guests – including family, friends, and neighbors, even two small children – were invited to replace the earth in its respective layers upon the bodies of the deceased, and cover the mounds above with flowers from the ceremony. The soil replaced, new life could grow from the nutrients given by the pet’s bodies and slowly the mounds would work their way back to ground level, as all becomes landscape again.

This slower process of grieving and returning life and death back to life reminds me of another ritualistic element of burials in Lesotho. Towards the end of my first year of service in the Peace Corps, I participated in the burial of someone I did know: one of my high school students. He was fifteen. One evening at a shop nearby, a man threatened the girl behind the counter with a gun, hoping to take what little cash was in her register, and my student stepped between them. I learned of the incident the next morning. The tradition in Lesotho, after a person is buried, is for family and sometimes close friends to shave their heads in mourning. Modern conventions have allowed for simply cutting a lock of hair, but I opted for the original practice, and shaved my whole head with a straight razor the morning after the burial. The physical reminder keeps the grief close and in-process, while the new growth of hair was a reminder to me to let go, and let life go on. Having witnessed quite a range of burial practices from many different spiritual and cultural traditions out at Carolina Memorial Sanctuary, I am continually reminded of the miracle of community, and the importance of not burying our own thoughts and emotions with the bodies of our loved ones. We need the support of and connection with those we love, and we need the intimacy of solitary process as we accept our own mortality and let go of those same thoughts and emotions.